Checking Websites’ GDPR Consent Compliance for Marketing Emails

Authors: Karel Kubicek karel.kubicek@inf.ethz.ch, Jakob Merane, Carlos Cotrini, Alexander Stremitzer, Stefan Bechtold, and David Basin

Abstract: The sending of marketing emails is regulated to protect users from unsolicited emails. For instance, the European Union’s ePrivacy Directive states that marketers must obtain users’ prior consent, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) specifies further that such consent must be freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous.

Based on these requirements, we design a labeling of legal characteristics for websites and emails. This leads to a simple decision procedure that detects potential legal violations. Using our procedure, we evaluated 1000 websites and the 5000 emails resulting from registering to these websites. Both datasets and evaluations are available upon request. We find that 21.9% of the websites contain potential violations of privacy and unfair competition rules, either in the registration process (17.3%) or email communication (17.7%). We demonstrate with a statistical analysis the possibility of automatically detecting such potential violations.

- Conference page: PETS 2022

- Download author pre-print of the paper: PDF

- Presentation: Google slides

- See full conference talk: youtube

- Request the datasets, source code, and supplementary material

Bibtex

@article{kubicek2022checking,

title={Checking Websites' {GDPR} Consent Compliance for Marketing Emails},

author={Karel Kubicek and Jakob Merane and Carlos Cotrini and Alexander Stremitzer and Stefan Bechtold and David Basin},

journal={Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies},

volume={2022},

issue={2},

pages={282-303},

year={2022},

publisher={Sciendo},

doi={10.2478/popets-2022-0046}

}

Websites are sending unsolicited emails

To register for web services, users generally must provide their email addresses. Unfortunately, this information can be used by companies to send unsolicited marketing emails, advertising their products and services. Given how common this practice is, users often do not remember ever registering for a service. Countries counteract these practices by regulations on privacy (GDPR, ePrivacy Directive) and unfair competition (Unfair Competition Act). In this work, we analyze the effectiveness of these regulations.

- We studied 1000 websites, successfully registered to 666 of them and received over 5k emails.

- We designed a legal taxonomy and annotated the registration forms of these websites and emails.

- We observed potential violations on over 22% of websites. Across the various violation types, we observed 119 consent and 162 email violations.

- We propose how to automate our violation detection procedure.

Annotated dataset

We explain the content of individual datasets below. Note that the dataset is upon request (form), as it contains sensitive data about the websites.

666 websites

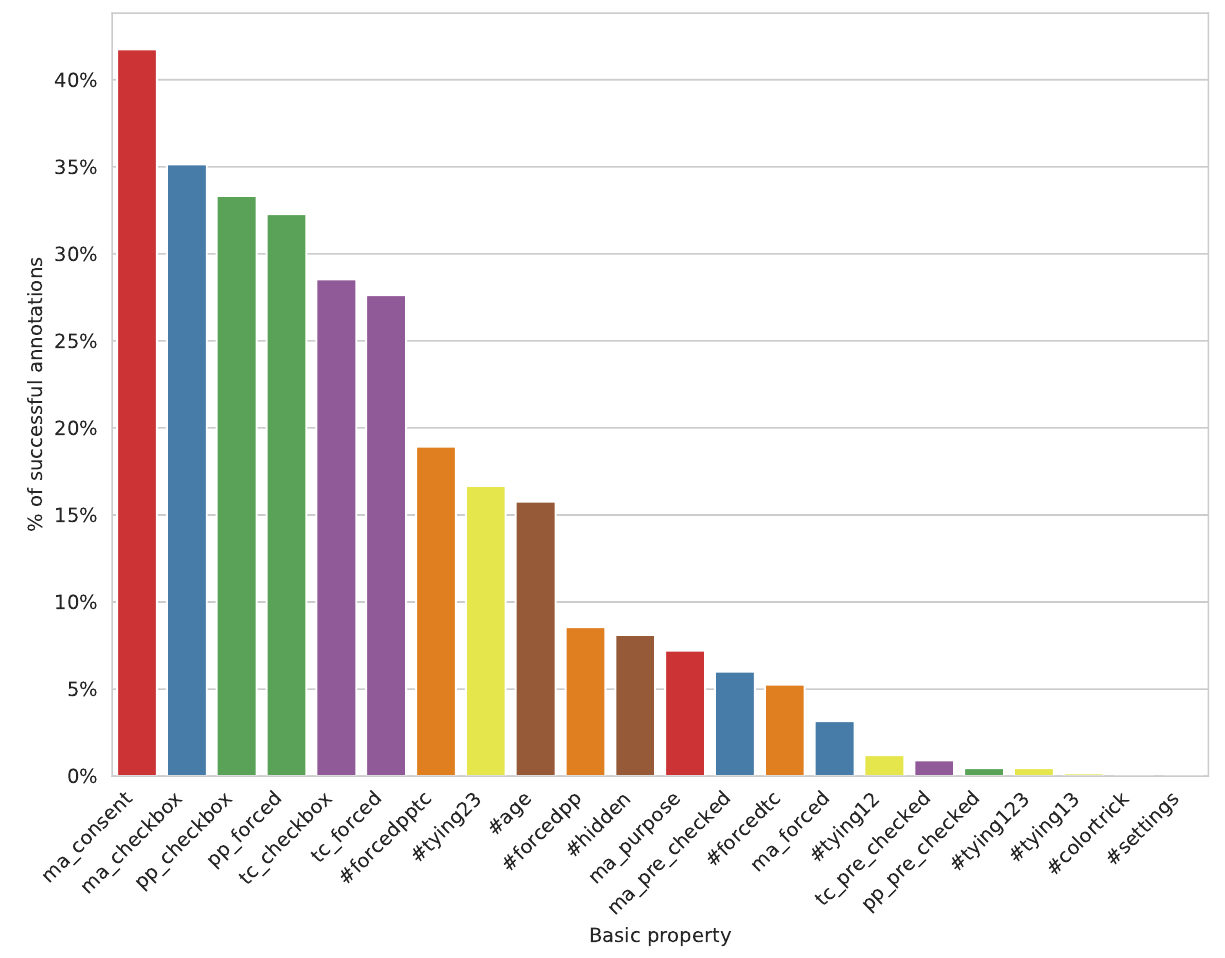

From 1k English and German websites, it was possible to register to 666 of them. Our legal assistants annotated these websites with 21 legal properties, like:

- Marketing consent: The website asks for consent from the user for marketing emails on the registration page.

- Marketing checkbox: There is a checkbox that the user must tick to give consent for marketing emails.

- Pre-checked checkbox: The corresponding checkbox (marketing/terms/policy) is already ticked by default.

The overview of the annotated properties in the 666 websites where annotators successfully registered.

The overview of the annotated properties in the 666 websites where annotators successfully registered.

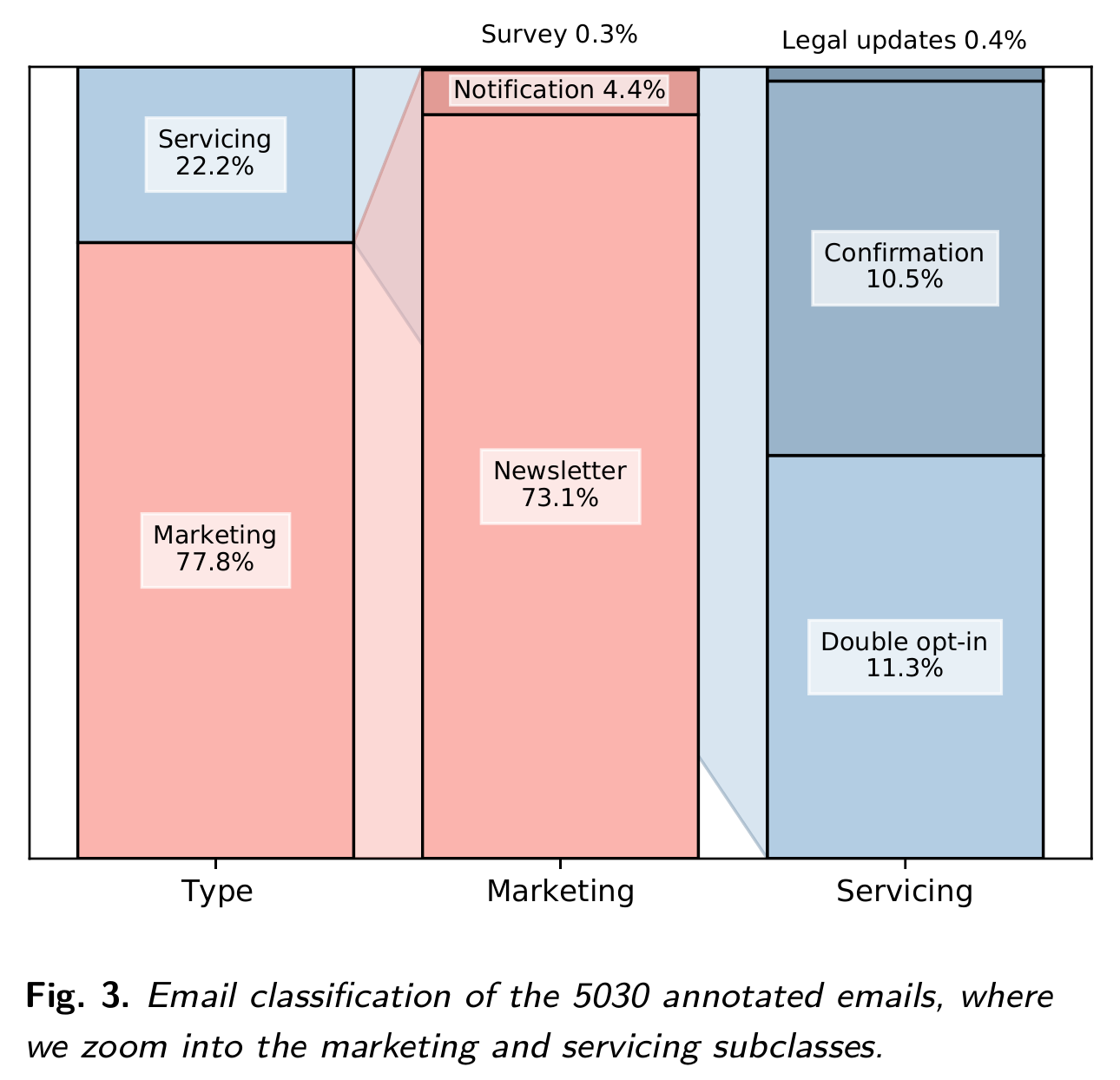

5k emails

For each annotation, we created an unique email address such that we can link all emails to the website where we registered. We received about 10k of emails, of which we annotated 5k of them with their purpose.

We also checked if the emails contain legal notice, unsubscribe links, user-provided passwords in plaintext, and if the email address was used by multiple parties (third-party sharing).

Observations

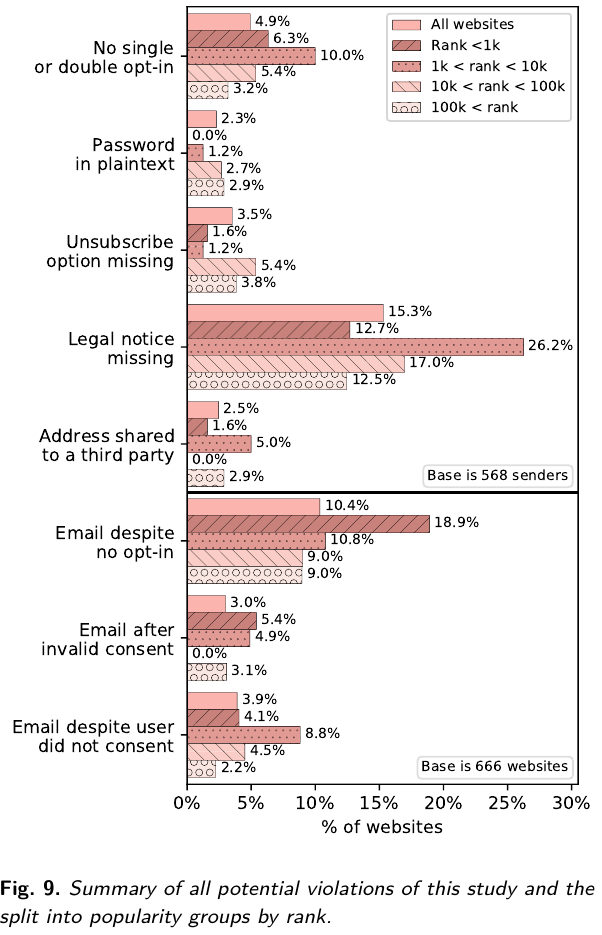

Using the legal properties, we are able to decide three potential violation types of the consent for sending marketing emails. In the email, we define further five types of potential violations.

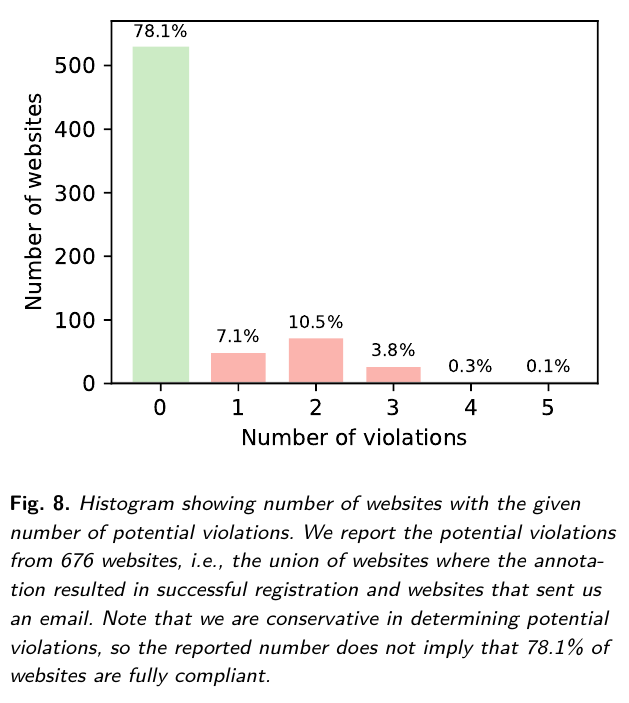

On the left is the summary of all violation types inspected in this study, split according to websites’ Alexa rank. On the right is the histogram of all websites in our study.

On the left is the summary of all violation types inspected in this study, split according to websites’ Alexa rank. On the right is the histogram of all websites in our study.

Limitations

Our work is limited in the following aspects.

- The sample of 1k websites might not be large enough to show representative statistics (especially for the rank analysis). In addition, our pre-filtering might have influenced the content of the dataset, which we tried to clarify ex-post in Sec. 3.1. Lesson learned is that we should have analyzed pre-filtering ex-ante on the pre-study data.

- For some services we have registered only once (when annotators disagreed), or in some cases we registered to different services of one website (newsletter subscription and full profile registration). This might influence the reported results.

- The automation of email processing might have resulted in failure to confirm some registrations. We analyze this in the Appendix A.2.2, but this observation is drawn on data that we also used to extend these registration confirmation scripts (it is not an independent evaluation set).

- Two most common potential violations in email content are analyzed only in the marketing emails (unsubscribe and legal notice). This is due to the nature of our study, where we did not sign up for marketing emails unless this was the only option (newsletter subscription). Therefore, the number of observed potential violations for these properties might be misleading when we use the base of all email senders, but we did not want to confuse the reader with even more varying set sizes. If we focus only on senders of marketing emails, over 3/4 of them fail to include proper legal notice and give users a chance to unsubscribe.

- The automation presented in this work is only a proof-of-concept, and it served as a proof of usefulness of the datasets.

Future work

We automate the violation detection, the work analyzing compliance of 660k websites is published at The Web Conference 2024, see this post.

Q&A

-

Q: Why there are so few violations and what do you mean by the potential violation?

A: Our study is purposefully conservative in reporting violations to limit false accusations of violations. This still resulted in 17.7% of websites sending emails without consent. Email content is even more often violating the regulations, but we received marketing emails only from websites that either violated consent, or their sole purpose was sending newsletters, which reduced the number of websites we could inspect.

We call violations potential for three reasons. First, as a matter of legal formality, only a legal proceeding can determine a violation. Second, while we were conservative in defining the types of potential violations, and our analysis is informed by the relevant statutes, judicial precedent, and articles by legal experts, there remains some legal uncertainty as to how courts will decide specific cases. Third, we faced factual uncertainties during our assessment. This is addressed in the appropriate sections. We remain confident that possible labeling disagreements are not of a magnitude or type that should affect our reported results.

-

Q: Did you report your findings to regulatory authorities?

A: This is work in progress, we aim to cooperate with regulatory authorities to enforce the privacy that users deserve. Nevertheless, if you observe similar privacy violations by websites, you can report it to local data protection authority.

-

Q: Can I use your violation detection procedure to scan a website for violations?

A: Not now. We need to automate the whole process of registering to websites and detecting the violations. We are working on that for future publications.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank:

- Martin Monsch, Patrick Krebs, Ozan Yildrim, and Nils Heinemann for their excellent legal research.

- Joachim Posegga for an access to a web proxy at the University of Passau.

- Reviewers for their feedback.

Updates

- August 17, 2022: Added talk recording and slides.

- March 10, 2022: Final version was published at PETS page, we updated the BibTex file.

- December 15, 2021: We submitted the camera ready version and released is as the author preprint.

- November 15, 2021: The initial version of this page.